Letterpress dates back to about 1040, when Bi Sheng invented movable ceramic type in China. Since then, not that much has changed.

In Europe, letterpress dates back to 1440, when Johannes Gutenberg developed movable metal type and the ability to (more) easily reproduce printed work was born. Today, we have the option of using polymer plates instead of metal type, but the overall process remains the same.

My press is a Kelsey Excelsior 5x8.” Though my particular model is from the 1980s, nothing is substantively different about it compared to the first models from 1872.

Since this press is 100% manual, I hand load each sheet of paper and then press down the handle for each print (it’s quite the workout!). This causes the rollers to travel over both the ink and printing plates before pressing the platten (with the card) on to the chase (with the plate). This transfers the ink to the page and creates a subtle deboss effect. Each colour of each card requires a separate trip into the press.

Interestingly, the letterpress printers of yore considered that deboss to be a printing fault, but it’s much loved by today’s customer! I try and strike a balance with small spots of debossed ink and larger kiss printed areas.

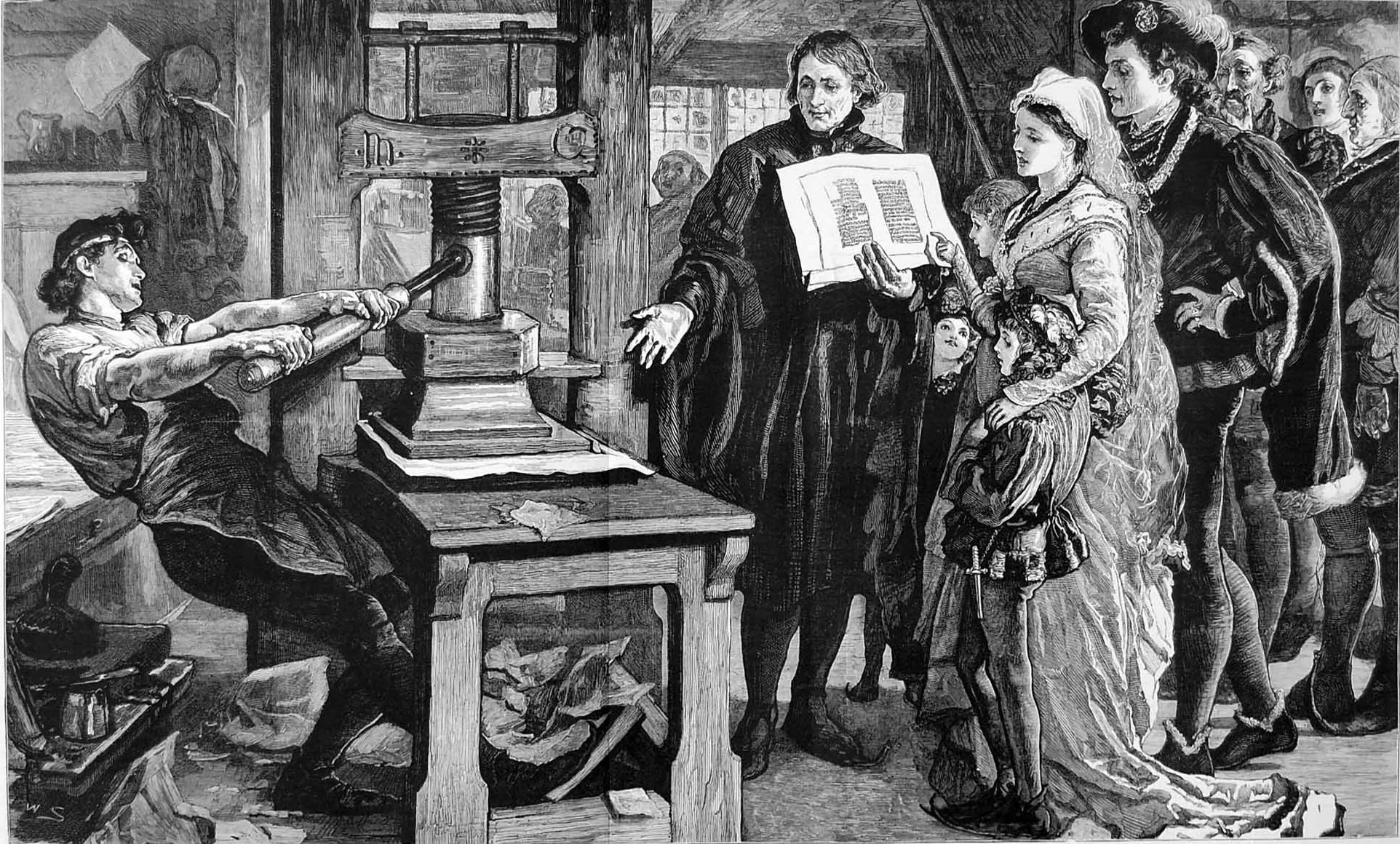

While I don’t have to work quite as hard as William Caxton in the image to the right, it’s still a workout to send hundreds of impressions through the press in a session!

The Caxton Celebration—Wiliam Caxton showing specimens of his printing to King Edward IV and his Queen. Published in The Graphic, 30 January 1877. Public Domain

As with everything, letterpress has been effected by trends over the years. With the advent of computers and easier ways of producing and printing text, it’s no wonder its popularity plummeted in the 1970s. Enter Martha Stewart.

In the 1990s, Martha Stewart Living began publishing images of wedding invitations printed using letterpress techniques in the magazine, and in November of 2004 published the following quote: "Great care is taken in choosing the perfect wedding stationery—couples ponder details from the level of formality to the flourishes of the typeface. The method of printing should be no less important, as it can enliven the design exquisitely. That is certainly the case with letterpress." In part because of Martha’s championing of the art, interest in letterpress was revived in the US and the burgeoning ‘small press’ movement gained speed.

It’s a good thing.

What makes letterpress different?

Thanks to hand-printed nature of letterpress, each card will be very slightly different. While we aim to be as consistent as possible, alignment, ink coverage, and colour shifts slightly from card to card.

Letterpress ink is slightly translucent by nature, which means that we can layer colours by printing one on top of the other to get a third (ex: a yellow circle overlapping a blue one will give a green middle). This also means that sometimes you see the texture of the paper coming through the ink, especially where the design has a larger area of solid colour (called a flood). This only adds texture and charm, as far as I’m concerned, but is certainly something to keep in mind if you’re used to perfectly solid digital printing.

Since each colour is printed one at a time, our designs are also colour separated so that we can print each plate as needed (I prefer to go lightest to darkest), keeping in mind the potential for mixing colours to create new ones as discussed above. In the past, printers would have used cast metal type, hand set (in reverse); a truly tedious, challenging task. Today, while some printers still use traditional metal type (the Sacramento History Museum has a great Instagram account demonstrating this), many of the rest of us use photopolymer plates, a UV sensitive plastic that allows for a detailed design to be left raised on the plate while the rest of the plate is washed away in the development process. One thing remains the same as with metal type, though—the final part to be printed remains ‘type high’, or 0.918inches.

This precise measurement, combined with the adjustment of packing and tightening screws, allows printers to tweak the amount of pressure between the paper and the plates. More pressure generally means a deeper indent in the paper, but can also give a squished, ‘muddy’ cast to the print (and is much harder to physically print, as well—you’re pushing down far more weight!).